Teaching Emotional Regulation with ABA Tools

Teaching Emotional Regulation with ABA Tools

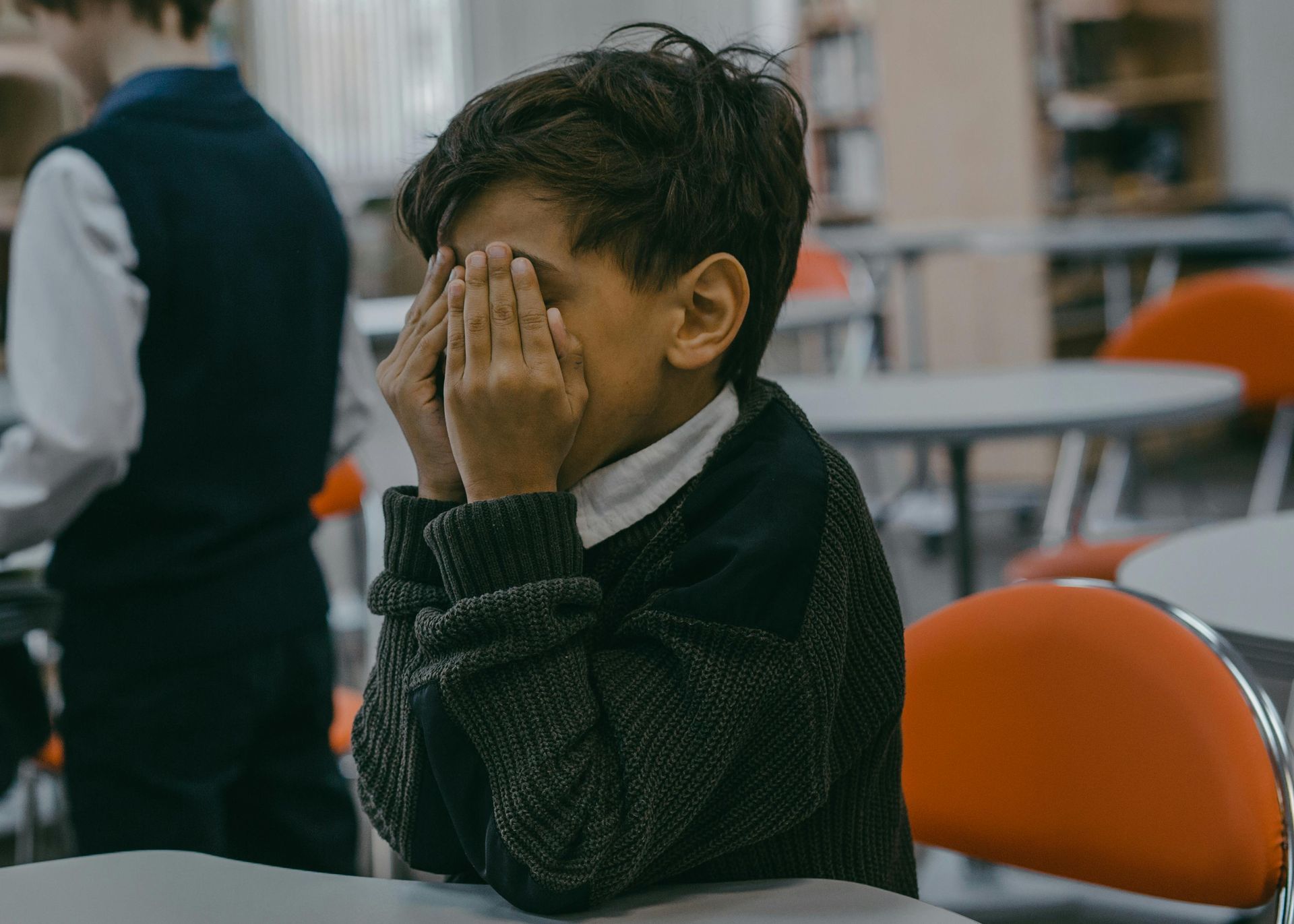

Emotional regulation is a critical skill that allows individuals to recognize, manage, and respond to their emotions in socially appropriate ways. For individuals with developmental disabilities, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), emotional regulation can be particularly challenging. Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) offers evidence-based tools and strategies to teach emotional regulation effectively. By leveraging the principles of ABA, practitioners can help individuals develop self-control and resilience, promoting success in various life domains.

Understanding Emotional Regulation

Emotional regulation involves the ability to monitor, evaluate, and modify emotional responses to meet the demands of a given situation. It encompasses recognizing emotions, understanding their causes, and implementing strategies to manage them. For individuals with ASD, emotional regulation difficulties may manifest as heightened reactivity, impulsivity, or meltdowns when faced with stressors. These challenges are often rooted in difficulties with communication, sensory processing, or coping mechanisms.

ABA interventions focus on breaking down emotional regulation into teachable components, using reinforcement and other behavior-modification techniques. The goal is to equip individuals with the tools they need to navigate emotional experiences and respond constructively.

The Role of ABA in Emotional Regulation

ABA emphasizes observable behaviors and their environmental influences. Emotional regulation, while internal, can be addressed by teaching behaviors that demonstrate self-regulation. For example, instead of teaching a child to “feel calm,” ABA might focus on behaviors like deep breathing, requesting a break, or using a calm-down area. These tangible actions serve as proxies for internal regulation and can be reinforced through ABA strategies.

A key component of ABA is identifying the antecedents and consequences of behaviors. For emotional regulation, antecedents might include specific triggers like loud noises or changes in routine, while consequences might involve the individual’s reaction to those triggers. Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA) are often used to determine the purpose of behaviors related to emotional dysregulation, whether they are escape-motivated, attention-seeking, or sensory-driven (Hanley et al., 2003). This understanding informs the design of tailored interventions.

Teaching Emotional Recognition

The foundation of emotional regulation is the ability to recognize emotions in oneself and others. ABA practitioners often use visual aids, social stories, and role-playing to teach emotional recognition. Visual aids like emotion cards or charts with faces depicting different emotions can help individuals associate facial expressions with specific feelings. Social stories, on the other hand, provide narratives that explain emotions in various contexts, making abstract concepts more concrete (Gray, 2010).

Reinforcement plays a crucial role in teaching emotional recognition. For instance, when a child accurately identifies an emotion in a scenario, they may receive verbal praise or a preferred item. Over time, these reinforcements help solidify the connection between the emotion and its label.

Developing Coping Strategies

Once individuals can identify emotions, the next step is teaching coping strategies. Coping strategies are behaviors or techniques that help manage emotional responses effectively. Common strategies taught in ABA include deep breathing, requesting a break, using a stress ball, or engaging in calming activities like listening to music.

Task analysis is frequently used to teach these strategies. For example, deep breathing can be broken down into specific steps: inhale through the nose for four counts, hold the breath for four counts, and exhale through the mouth for four counts. Each step is taught sequentially, with reinforcement provided at each stage to ensure mastery.

In some cases, ABA practitioners may use video modeling, where individuals watch videos of themselves or others successfully using coping strategies. This approach has been shown to improve skill acquisition and generalization (Bellini & Akullian, 2007).

Managing Triggers and the Environment

A proactive approach to emotional regulation involves managing environmental triggers that contribute to dysregulation. In ABA, this is known as antecedent intervention. For example, if a loud classroom causes anxiety, strategies might include providing noise-canceling headphones or creating a quiet corner. By modifying the environment, practitioners can reduce the likelihood of emotional outbursts and set the stage for success.

Additionally, teaching individuals to recognize their own triggers is a vital aspect of emotional regulation. Self-monitoring tools, such as visual scales that indicate levels of stress or arousal, can help individuals identify when they are becoming dysregulated. This self-awareness allows them to implement coping strategies before emotions escalate.

Using Reinforcement to Promote Emotional Regulation

Reinforcement is a cornerstone of ABA and plays a pivotal role in teaching emotional regulation. Positive reinforcement involves providing a reward when an individual engages in a desired behavior, such as using a coping strategy. For instance, if a child requests a break instead of yelling during a stressful situation, they might receive access to a preferred activity or praise.

Differential reinforcement is another effective strategy. This approach involves reinforcing appropriate behaviors while withholding reinforcement for maladaptive behaviors. For example, a child might receive attention when they calmly ask for help but not when they scream. Over time, the reinforced behavior becomes more frequent, while the maladaptive behavior decreases.

Teaching Generalization and Maintenance

Emotional regulation skills must be generalized across various settings and maintained over time to be truly effective. Generalization involves ensuring that skills learned in therapy are applied in real-world situations, such as at home, school, or community settings. ABA practitioners often use naturalistic teaching methods, where skills are practiced in the environments where they are most likely to be used.

Caregiver training is a critical component of generalization. By teaching parents, teachers, and other caregivers to reinforce emotional regulation behaviors consistently, practitioners can ensure that individuals receive support across all contexts (Koegel et al., 1996).

Maintenance strategies focus on ensuring that learned behaviors are retained over time. This may involve gradually fading reinforcement or incorporating intermittent reinforcement schedules. For instance, a child who initially receives a reward every time they use a coping strategy might eventually receive rewards only occasionally, ensuring the behavior remains robust without constant reinforcement.

Measuring Progress in Emotional Regulation

Data collection and analysis are integral to ABA, providing a clear picture of an individual’s progress. Practitioners often use frequency counts, duration measures, or interval recording to track behaviors related to emotional regulation. For example, they might measure how often an individual engages in a coping strategy during a stressful situation or how long they remain calm after implementing the strategy.

Graphing this data allows practitioners to identify trends and adjust interventions as needed. If progress plateaus, they may modify the intervention by introducing new reinforcers, adjusting task difficulty, or addressing additional environmental factors.

Ethical Considerations in Teaching Emotional Regulation

Teaching emotional regulation involves ethical considerations, particularly when working with vulnerable populations. Practitioners must ensure that interventions are individualized, culturally sensitive, and aligned with the individual’s preferences and needs. The Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) outlines ethical guidelines that emphasize the importance of dignity, respect, and informed consent in all ABA practices (BACB, 2020).

Additionally, practitioners should avoid using punitive measures to address emotional dysregulation, as these can exacerbate anxiety and undermine trust. Instead, the focus should remain on positive reinforcement and skill-building strategies that empower individuals to manage their emotions constructively.

Conclusion

Emotional regulation is a vital skill that enhances an individual’s quality of life and ability to navigate social, academic, and personal challenges. Through ABA tools such as reinforcement, task analysis, and antecedent interventions, practitioners can teach emotional recognition, coping strategies, and self-monitoring skills. By promoting generalization and maintenance, these interventions ensure that emotional regulation skills are robust and applicable across diverse settings.

The success of these interventions relies on individualized approaches, consistent reinforcement, and collaboration with caregivers. With the support of ABA, individuals with developmental disabilities can develop the emotional regulation skills they need to thrive, fostering independence and resilience in the face of life’s challenges.

References

Bellini, S., & Akullian, J. (2007). A meta-analysis of video modeling and video self-modeling interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Exceptional Children, 73(3), 264–287.

Gray, C. (2010). The new social story book. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons.