Understanding Positive and Negative Reinforcement in ABA for Families

Understanding Positive and Negative Reinforcement in ABA for Families

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is a widely recognized and evidence-based approach for supporting individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other developmental differences. One of the core principles of ABA is reinforcement, which strengthens desired behaviors and encourages positive outcomes. Understanding positive and negative reinforcement can help families implement effective behavioral strategies at home, leading to meaningful improvements in their child's development and daily functioning.

Defining Reinforcement in ABA

Reinforcement occurs when a stimulus follows a behavior and increases the likelihood of that behavior occurring again in the future (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2020). Many parents may assume reinforcement only refers to rewards or praise, but reinforcement is a much broader concept that includes both positive and negative reinforcement. Both types are essential tools in ABA therapy and can be used strategically to shape behavior in children with ASD.

Positive Reinforcement: Encouraging Desired Behaviors

Positive reinforcement involves adding a stimulus after a desired behavior occurs, which increases the likelihood of the behavior happening again. For example, if a child completes their homework and is given extra playtime as a reward, the additional playtime serves as positive reinforcement. In this case, the child is more likely to complete homework in the future because of the reinforcing consequence.

Parents and caregivers can use various positive reinforcement strategies at home to support skill development and appropriate behavior. Common forms of positive reinforcement include verbal praise, tangible rewards, special privileges, and social reinforcement such as high-fives or hugs. The key is ensuring that the reinforcement is meaningful and motivating for the child.

For positive reinforcement to be effective, it should be immediate, contingent on the behavior, and consistently applied (Kazdin, 2017). If a child is working on requesting items using verbal language, reinforcing the behavior right after they correctly request will help strengthen their communication skills. Delayed reinforcement may not be as effective because the child may not associate the reward with their behavior.

Negative Reinforcement: Removing an Aversive Stimulus

Negative reinforcement involves removing an aversive stimulus after a desired behavior occurs, which increases the likelihood of the behavior happening again. Many people mistakenly associate negative reinforcement with punishment, but they are different concepts. Negative reinforcement strengthens a behavior by eliminating something unpleasant, whereas punishment decreases behavior (Miltenberger, 2015).

An example of negative reinforcement is when a child puts on their seatbelt to stop the car from beeping. The beeping sound is an aversive stimulus, and its removal encourages the child to wear their seatbelt in the future. Similarly, a child who dislikes loud environments may use noise-canceling headphones, reinforcing their behavior of seeking sensory regulation by escaping the overwhelming noise.

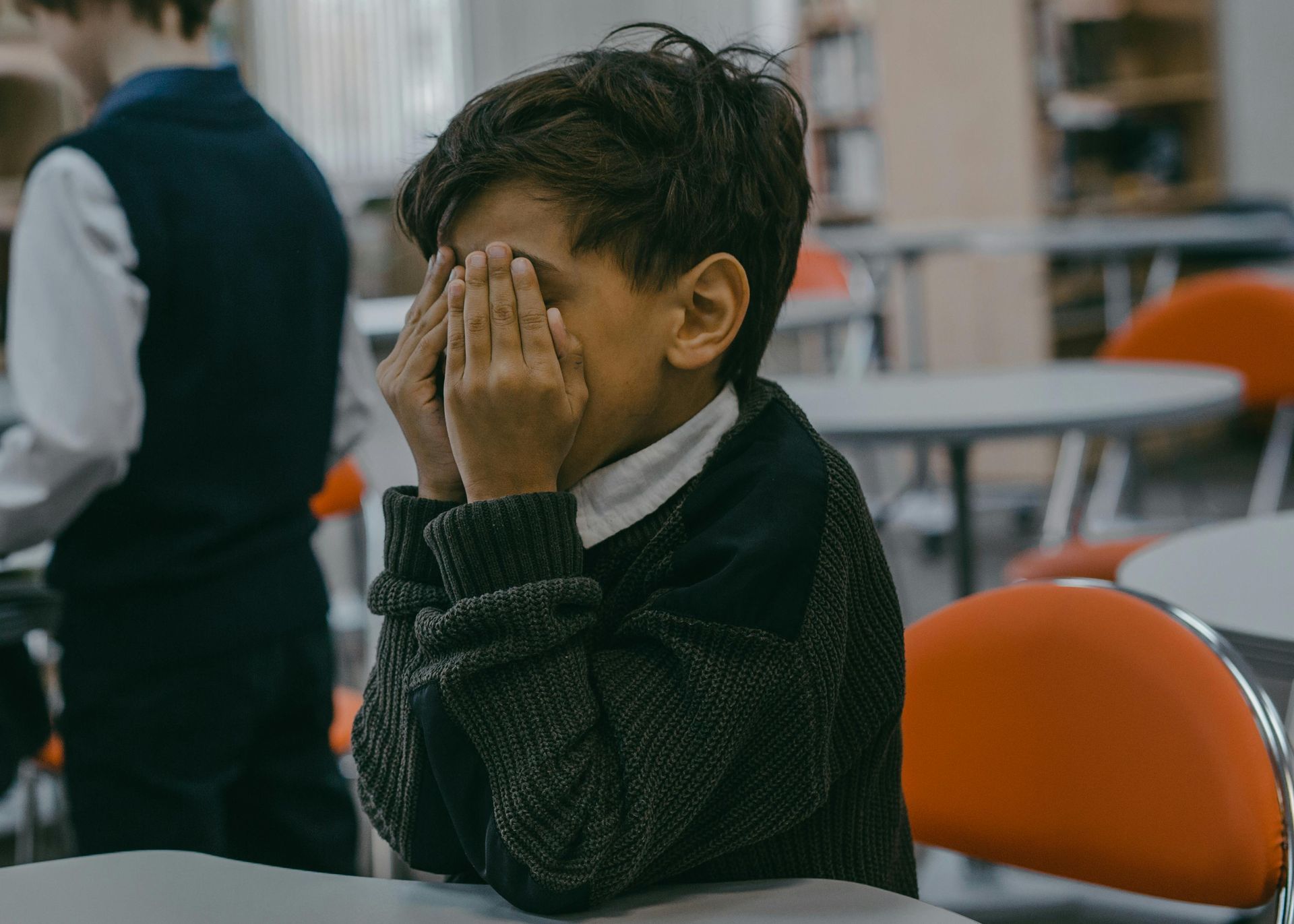

In the context of ABA, negative reinforcement is used strategically to help children learn adaptive skills. For instance, if a child engages in tantrums during a difficult homework assignment, a therapist may teach the child to ask for a break appropriately. Once the child learns to request a break instead of engaging in a tantrum, the removal of the aversive task (homework) reinforces the appropriate communication behavior. Over time, this leads to better self-regulation and coping skills.

Balancing Positive and Negative Reinforcement

Both positive and negative reinforcement are essential in ABA interventions. While positive reinforcement is often emphasized because of its ability to create enjoyable learning experiences, negative reinforcement can be equally valuable when used correctly. The key to effective reinforcement is ensuring that it aligns with the child's individual needs and promotes long-term skill development.

Parents and caregivers should observe their child’s responses to different reinforcement strategies to determine what works best. Some children may be highly motivated by tangible rewards, while others respond better to social praise or the removal of aversive conditions. The reinforcement should always be individualized to the child's unique preferences and needs (Vollmer & Hackenberg, 2001).

Potential Challenges in Reinforcement Procedures

Although reinforcement is a powerful tool, it must be applied correctly to prevent unintended consequences. One common challenge is the overuse of tangible reinforcement, such as toys or treats, which may lead to dependence on external rewards. To address this, parents can gradually fade tangible reinforcement and shift to more natural reinforcers, such as social praise and intrinsic motivation (Cooper et al., 2020).

Another potential issue is inadvertently reinforcing unwanted behaviors. For example, if a child cries when asked to complete a task and the parent allows them to avoid it, the child learns that crying leads to escape. In this case, negative reinforcement is unintentionally strengthening the problem behavior. To prevent this, parents should ensure that reinforcement strategies support appropriate and functional behaviors instead.

Implementing Reinforcement at Home

For families of children with ASD, incorporating reinforcement strategies into daily routines can create a more structured and supportive learning environment. Establishing clear expectations and consistently reinforcing desired behaviors can help children develop new skills and improve social interactions.

One effective approach is using reinforcement schedules, such as continuous reinforcement (providing reinforcement every time the behavior occurs) or intermittent reinforcement (reinforcing the behavior occasionally). Continuous reinforcement is useful when teaching new skills, while intermittent reinforcement helps maintain the behavior over time (Kazdin, 2017).

Visual supports, token economies, and behavior charts are also helpful tools for implementing reinforcement at home. A token economy system, where a child earns tokens for positive behaviors that can be exchanged for a preferred item or activity, is a structured way to provide reinforcement. Visual schedules can help children understand expectations and transitions, reducing anxiety and promoting independence.

Conclusion

Reinforcement is a fundamental component of ABA that can significantly impact a child's ability to learn, communicate, and engage with their environment. By understanding the principles of positive and negative reinforcement, families can implement effective strategies that promote skill development and positive behavior change. Whether through the addition of preferred stimuli or the removal of aversive conditions, reinforcement plays a crucial role in shaping behavior and enhancing the quality of life for children with ASD and their families. When applied consistently and thoughtfully, reinforcement procedures empower children to reach their full potential and navigate their world with confidence.

References

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Kazdin, A. E. (2017). Behavior modification in applied settings. Waveland Press.

Miltenberger, R. G. (2015). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Vollmer, T. R., & Hackenberg, T. D. (2001). Reinforcement contingencies and their application in applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(4), 483-486